Shawn Hausman reflects on AREA, a club in constant reinvention

In this exclusive interview, the legendary designer discusses shaping immersive worlds before cell phones, knowing when to walk away, and what it really means to design with a point of view.

This post may be too long for email, read on web for the best experience.

I’ve been obsessed with The Standard Hotels since I was a kid. My grandma used to take me to the Grill at the high-line location for cookies and milk in the early 2010s. In college, I dreamed of working at their corporate office. I’ve even waxed poetic about the group here on Substack.

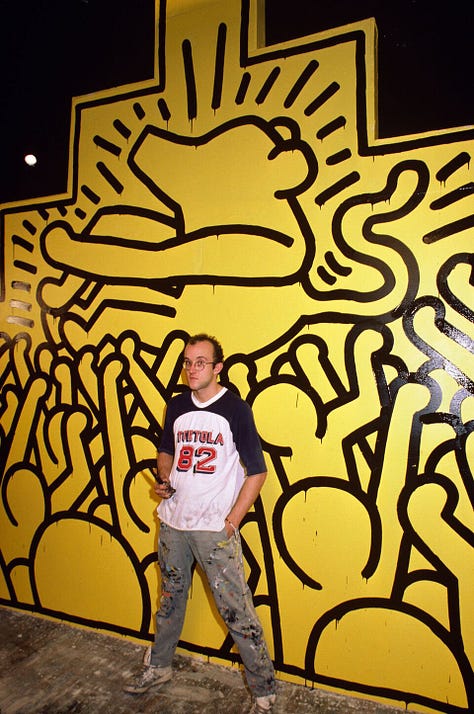

Earlier this month, I posted a series of videos about AREA, the nightclub Shawn Hausman co-founded long before designing the interiors of André Balazs’ global hotel group. It changed themes every six weeks, ran like a film set, and sent out elaborate invites in eggshells and mousetraps. Those videos now have more than a million views, with comments asking, “Where’s the documentary?” I replied: “You’re watching it.”

AREA existed before the internet, and its best details live in stories, not search results. Some of them even surfaced in my comments. I kept digging, reached out to Shawn, and we got on the phone.

What follows is that conversation.

A rare interview with someone who has never chased attention, but shaped the way we experience spaces. We talk about the actual logistics involved in keeping up with the club’s ambitious reinventions in a time before the internet, knowing when to leave something behind, and why true originality isn’t necessarily about making something new, but how you make it yours.

Emma Apple Chozick: I’d love to start at the beginning. What inspired AREA? How did it come together?

Shawn Hausman: There were four of us: myself, Eric Goode, Christopher Goode, and Darius Azari. We didn’t think of ourselves as businesspeople. It felt more like a rock band. We had no idea how to run a club, we just had this thing we wanted to do.

Before New York, we had thrown some parties in California, kind of inspired by 1960s happenings. We’d build these immersive environments out of whatever we could find. It was all scavenged, all handmade.

Eric [Goode] and I were obsessed with nightclubs. Anytime we traveled, we’d check out the club scene, not in a formal way, just trying to figure it all out. This was mid-’70s. Disco was just starting to take off.

We were young, so we could only really get into gay clubs, places that didn’t card. We always knew we wanted to do a club eventually.

I moved to NYC, and Eric and Chris followed. We opened an after-hours club, no name, no money. We were open two nights a week, and we changed the whole space each time. That was kind of the prototype for AREA.

“It felt more like a rock band. We had no idea how to run a club—we just had this thing we wanted to do.”

After that, we started looking for a permanent space. It was hard to get a landlord to trust a bunch of kids. We almost signed a place in Midtown, an old General Tire building, but it didn’t feel right, and we realized we needed to be downtown.

Then we found the building on Hudson Street. The landlord was this eccentric guy, Howard Rower. His buzzer had like 30 different business names on it, probably because he was getting sued all the time. He was married to [Alexander] Calder’s daughter, Mary.

He’d been burned by another nightclub tenant, but eventually, he said, “You guys seem like good kids,” and he gave us a shot.

EC: And you didn’t have investors, right?

SH: No. We had no money. So we made these black boxes, maybe six or eight. Totally handmade. Inside was a red button that played a tape loop of a woman with a British accent giving instructions. There were hidden envelopes inside: one with our bios, one with the concept, etc., you had to open them in a certain order. It was like this little mystery experience.

We sent them to anyone we thought might fund us, people we barely knew. We didn’t raise a dime from these boxes, and eventually found a few investors.

“We didn’t raise a dime from these boxes. But that kind of mystery, and the way you had to experience it, that’s really what AREA became about.”

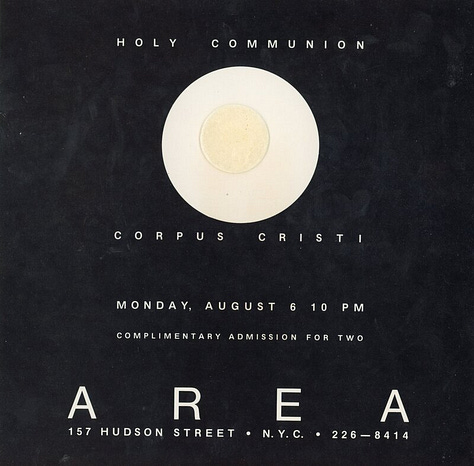

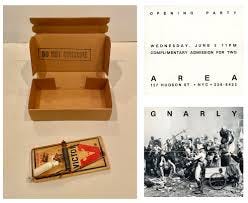

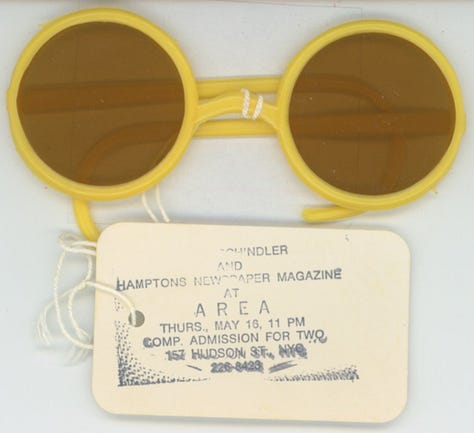

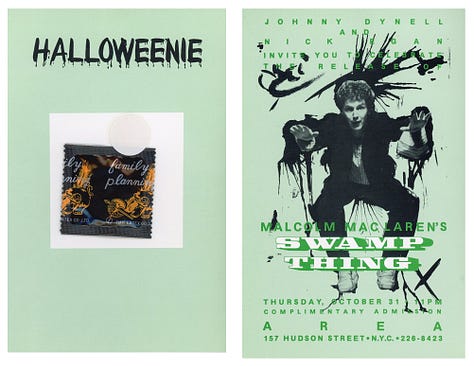

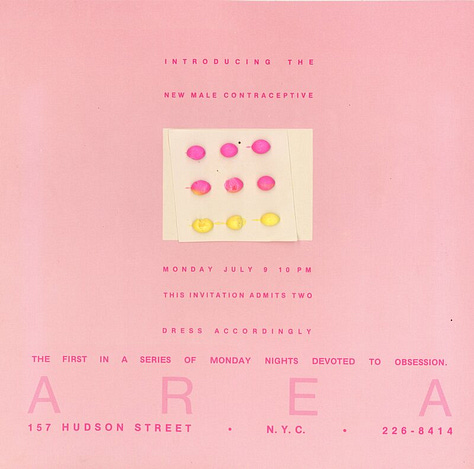

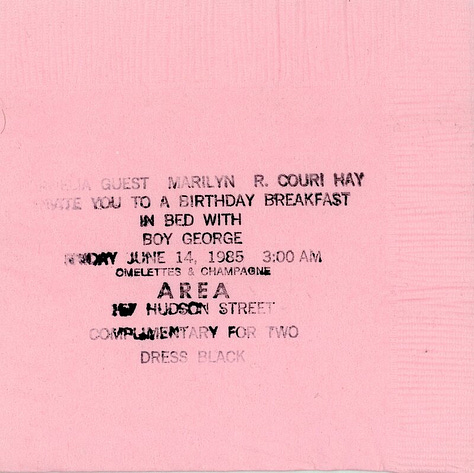

EC: The invitations became part of the show. How did that start?

SH: We mailed out around 5,000 for each theme. No email back then, just physical objects that had to make people want to come.

They were crazy. For the Elements theme, there was a matchbook with flash paper you had to light to reveal the invite. For Gnarly, a mousetrap inside with an ammonia capsule. When you opened it, it snapped and released this sharp smell. Underneath was a group photo of a bunch of us dressed like Mad Max characters.

For Natural History invite, we drilled tiny holes into real eggs, blew out the yolks, speckle painted every one, and tucked a scroll inside. We placed each in a little shredded-paper nest.

The logistics were intense. We hand-set 5,000 mousetraps. We had a drill press for the eggs. Then we’d load everything—hundreds of boxes—into this beat-up work truck and drive them to the post office. Giant canvas mailbags full of strange objects. Jennifer, Eric’s sister, and Chris usually did the drop-offs. The post office must’ve hated us, but somehow it all went through.

“We drilled tiny holes into real eggs, blew out the yolks, painted every one, and tucked a scroll inside.”

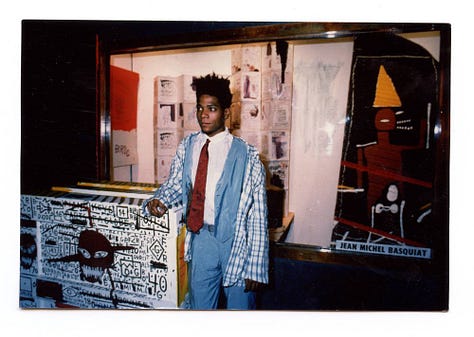

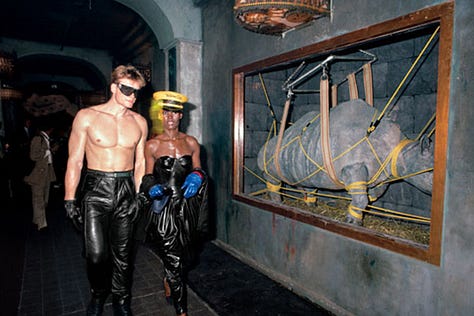

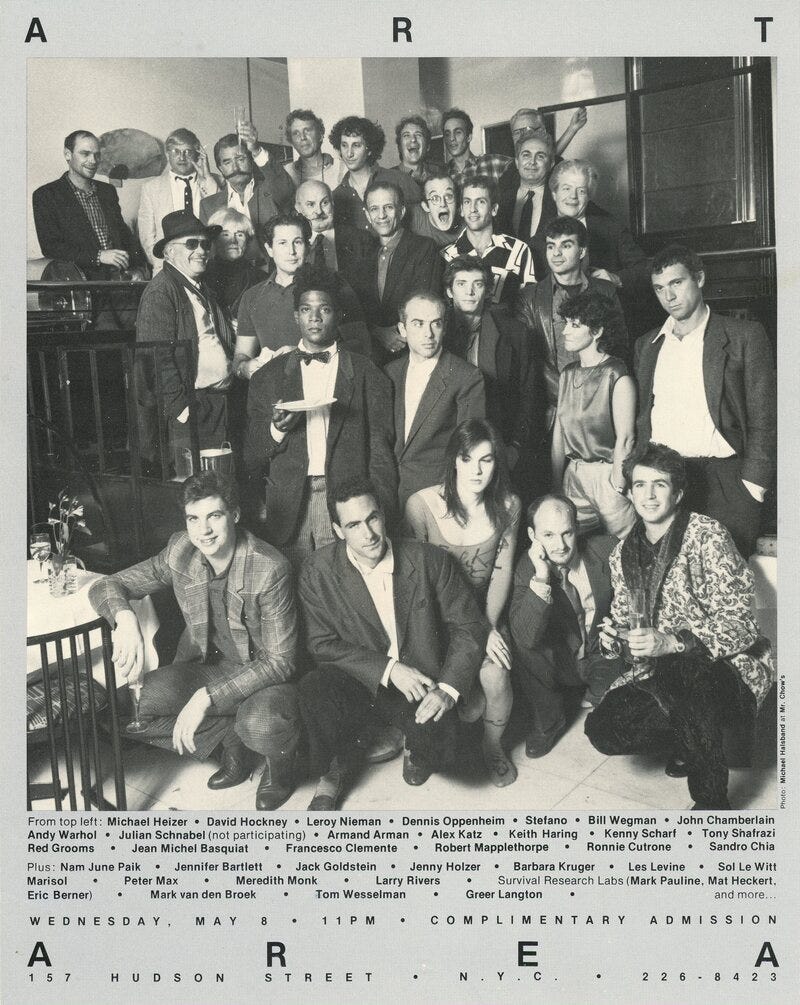

EC: And who were you sending them to? What was the crowd actually like?

SH: That’s the funny part. Everyone talks about the invitations, but that wasn’t the only way to get in. The guest list was totally separate and this was the time in NY when the doorman had all the power. We invited who we wanted—friends, artists, downtown people. And if your name was on the list, you didn’t need the physical invite. It was really about the energy in the room.

“Everyone talks about the invitations, but that wasn’t the only way people got in. It was really about almost curating a group of people to create the energy in the room.”

EC: You were rebuilding the club every six weeks. How did that even work?

SH: We were open four nights a week and closed three. Every six weeks, we’d use those three days to tear everything out and build something new. Full changeover. New theme, new installation, new dioramas, painted backdrops—everything.

The pressure was real. By day three, it always felt like it wasn’t going to happen. Everyone was exhausted, up for three days straight, scrambling to finish. There was always this moment of, “We’re not going to pull this off.” And then somehow, we would.

It taught me what’s actually possible in 24 hours. That’s something I’ve carried with me ever since. Like, don’t tell me it can’t be done, I’ve seen what’s possible in a day.

“By day three, it always felt like it wasn’t going to happen. And then somehow, we would.”

EC: Where were you getting all the materials?

SH: One thing we hadn’t thought about when we picked the space—but turned out to be huge—was how close we were to Canal Street. Back then, it had everything: plastic suppliers, foam, scrap metal, electronics, all kinds of weird junk.

People were constantly running back and forth. You’d pass someone from the team on the street with bags of stuff. We weren’t that organized and we didn’t have cell phones. So if someone bought the wrong thing, you couldn’t call them. You just had to walk back.

This was pre-FedEx too. We were using phone books and business pages. We had phone books for every state in the US. Jessica was in charge of handling research.

EC: How big was the team actually making all of this happen?

SH: At one point during a changeover, maybe 40 people. It was a real mix. We had a few key really talented people that led the art department with Jennifer: Serge Becker, Kenny Baird, Mark Garbarino.

Each of us—me, Eric, Darius, Chris—would take on different windows or parts of a theme. Sometimes because it was your idea, sometimes just because someone needed to do it.

I soon realized I was better at directing a group than building something on my own. I could delegate, problem-solve, move things forward. That was something I figured out back then, and it stayed with me. Even if you plan everything, it never goes exactly how you expect. You have to adjust as you go.

“I could delegate, problem-solve, move things forward. That was something I figured out back then, and it stayed with me.”

EC: Did you feel like you were trying to stand out from the other clubs downtown?

SH: A lot of the East Village clubs back then were kind of thrown together. There was a charm to it, but we wanted something more polished. Still weird, still funky, but better executed.

We cared about how things looked. We wanted it to feel elevated, even if it was temporary. Everything went back into the themes. All the money we made got recycled into the next one. We weren’t driven by profit.

EC: So AREA wasn’t a business?

SH: Not at all. We didn’t really know what we were doing from a financial standpoint. We didn’t realize how much money clubs could make from private events and rentals. That wasn’t part of our setup.

All the money went back into the themes, the invites. We paid ourselves small salaries, but that was it. When the club finally closed, I think we actually had to chip in to cover back taxes.

“We paid ourselves salaries, but that was it. When the club finally closed, we had to chip in to cover back taxes.”

EC: But from the outside, it must’ve looked like you were doing really well.

SH: Yeah, that’s the thing. People thought we were making a ton of money because AREA was so popular and ‘successful.’ So you’d go out to dinner and everyone expected you to pick up the check.

But we were just paying ourselves basically enough to live. We were the operators, running the club ourselves.

We had a whole system: two people worked nights, two worked days, and we rotated every two weeks. Chris figured it out. You’d also rotate who you were working with, so it kept things balanced. It meant we were all involved in the day-to-day, not just showing up at night. It was a real rhythm.

“AREA was so popular and ‘successful.’ People thought we were making a ton of money. We weren’t.”

EC: The club closed after only four years. There seem to be a lot of theories about why you didn’t keep going, what was it?

SH: From the beginning, we said we’d only do it for two years. That was the plan. When we got to that point, the investors wanted to sell, but it didn’t really make sense without us running it.

We tried to keep it going for a bit, but New York was changing. Palladium opened. Nell’s opened. The scene got bigger, flashier. It wasn’t our moment anymore.

Darius and I moved to LA. Eric and Chris kept it open a little longer. That kind of energy is hard to sustain. It had run its course.

“From the beginning, we said we’d only do it for two years. That was the plan.”

EC: Is that when you started working with André Balazs?

SH: Yeah, I had met André through Eric—he was involved with MK, Eric and Serge’s club. Later, in LA, Andre asked me to do a model room at the Chateau. He’d already gone through a couple designers and wasn’t happy with where it was headed. I did one room, and that’s what started our working relationship.

EC: Had you done interiors before that?

SH: Before that, I’d done one interior—Hollywood Canteen, this place in LA Darius and I did it together. We took over this old coffee shop and totally redid it. No permits, nothing official. We even brought in scenic artists to “age” the pipes so it looked like everything had always been there.

That was probably the first time I started thinking about real spaces the same way I thought about a set. And that stuck with me. I still don’t just design something for aesthetics. It has to have a narrative. So I’ll come up with some fictional backstory—a character who inhabits the place—and that helps everything make sense for me. Otherwise, it just looks like objects placed on a shelf. It has to feel lived in. That’s what I care about—creating something with a logic behind it. Even if no one else knows the story, I need to know it.

“I still don’t just design something to look nice. It has to have a story.”

EC: That sense of personal logic—of building a world on your own terms—feels like it’s been there from the beginning. What would you say to hundreds of commenters inspired by that? Who want to do what you did?

SH: Honestly, I still feel like I’m just kind of faking it. I never formally studied any of this. I think the most important thing is perspective. Everyone has—or should have—their own way of seeing things. And that comes from your life, your experiences, your background. We’re all different, so if you can apply that uniqueness as your point of view, it becomes something distinct.

I’m always pulling references from the past, from all kinds of stuff. People say nothing’s new, and maybe that’s true—but the way you put things together, that’s where the originality comes in.

“What you choose, what you combine—that’s what makes it yours.”

In school, what always struck me was how everyone got the same assignment, same resources, but came back with completely different results. That really stuck with me—how we all look at things in our own way. That’s where the interesting stuff comes from.

Incredible read. Loved this !

Loved this